I suppose it was

commercial publishers who invented the genre novel as something which could be

packaged and sold as Crime, Mystery,

Horror, Romance ….. That packaging created a handy distinction between

low-brow and high-brow literature. Those who regarded themselves as above Genre

novels could simply walk away from shop shelves labelled with those identifications. Bloomsbury never

became a Genre section though it clearly is for many readers.

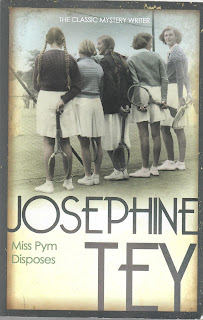

The novelist Josephine

Tey (1896 - 1952) - also known as the

playwright Gordon Daviot (author of

Richard of Bordeaux 1932) but rarely as the Miss Elizabeth Mackintosh of her Times obituary - was shelved as a Crime

writer rather as John le Carré was later assigned to Spy fiction. Josephine Tey

probably didn’t mind very much since she wrote, she said, for fun. At page 178 of Miss Pym Disposes, her friend Henrietta puts down Miss Pym - who

could well be taken as the alter ego of Josephine Tey - as having “an

extraordinarily impulsive and frivolous mind”. (Tey, incidentally, had just

pointed out to the reader that Henrietta has missed an allusion to Kipling’s “Make me different from all other animals by five this afternoon”).

I read first The Franchise Affair and now Miss Pym Disposes in both of which the

author has lots of fun. She can be eccentric, whimsical, acid, thoughtful…as

the mood takes her. And to that degree she doesn’t seem to care very much who is looking over her

shoulder. That seems quite admirable.

Most maybe all authors

have at least one or two people peering over their shoulders. The obvious one

is the combined double-headed figure of publisher and censor who will put a

stop to things currently disapproved of so there is no point in writing them

down now only to have them taken out later. At page 10 in my copy Miss Pym is

rudely awakened by unwanted noises and “said something that was neither civilised

nor cultured and sat up”. The trick here is to leave it to the reader’s

imagination and let them pick between “What the devil?" and “What the fuck?” Kipling uses

the same trick in Kim as I previously

discussed elsewhere on this Blog. Leaving it to the reader avoids the humiliation of the dashes which

litter Victorian novels, usually following the letter D, and the childishness

of those carefully calculated modern

asterisks designed to allow you to retrieve the word intended. We are all so

adept at this now that in context (for example, as spoken by Boris Johnson) we

will know exactly what is intended by ****. But if we don’t already know the words

of Philip Larkin’s This Be The Verse -

and American freshmen students often won’t - then the internet versions of the

poem available may well leave us puzzled as to what it is that your parents

do to you. That is not a good state to be in if you have an essay to write..

But Josephine Tey is

not troubled by the more extensive and ever-expanding modern sensitivities

which authors now have to pre-empt. Fortunately, she has recently come out of

copyright and so the old Copyright holders (The National Trust) can no longer authorise or require bowdlerised versions of her novels.

I don’t propose to offer a list of things which some enterprising corporate publishing censor might now use as a

crib. It would be a long chore anyway, if nothing more. You have been

trigger-warned and that ought to be enough.

But the second person

at the shoulder is what for short might be called the author’s super ego: the

rather punitive figure on the look-out for guilty secrets, the search for

pleasure, shameful revelations and such like. Josephine Tey - who all the

sources say was a very private person - may have had a fairly active super

ego. I wait to read the biography by Jennifer Morag Henderson [ See now the footnote to this Blog post]. Miss Pym Disposes published in

1946 is set in an all-female establishment where live-in teenage girls learn

gymnastics, dancing, outdoor sports, massage therapies and more under the

supervision of a staff of live-in unmarried women. The scope for writing a

novel in the genre of Lesbian fiction or simply Erotic fiction is enormous and

modern super ego sensitivities would oppose not much of a bar to making use of

the opportunity, provided political correctness was maintained.

It’s true that the

tragic events which conclude the novel arise from the conjunction of two sets

of complex relationships: on one side the misplaced favouritism of the college

Principal for an unappealing and dishonest student; on the other the close relationship

between the most brilliant student Mary Innes and her beau Pamela Nash, nicknamed Beau Nash. They are planning to

celebrate their graduation by going off to Norway together. But what might seethe beneath the surface is left to the reader to infer or imagine. However, on the surface and in very marked contrast, the novel is open about the successful

heterosexual relationship which develops between an outsider Brazilian student, the colourfully dressed

Desterro (who the college girls nickname The

Nut Tart) and the very decent young mixed-ethnicity (Brazilian- English)

man Rick. Desterro has to live with the college girls calling

him her gigolo.

The only erotically

explicit passage in the novel depicts at some length (pages 216-17) a solo dance

which Desterro performs to a public audience which includes Rick. At the end,

the audience clap “like children at a Wild West matinée” (217). And, Reader, at

page 245 she marries him. The novel ends at page 249.

One might say that this

spoken love story provides a structural counterpart to unspoken repressed

desire which runs through the main narrative. But whether that is or isn’t a

reasonable way of putting the novel in context, I found the novel absorbing and

striking in its language, its metaphors and comparisons. An author who can

imagine The Nut Tart as a nickname

which girls in a Physical Training establishment could pin on one of their

number must have something going for her.

Footnote

No comments:

Post a Comment